Special Serengeti

- Jan Dehn

- Jun 27, 2025

- 5 min read

They say Serengeti shall never die, but judging by what is happening to wildlife and environment in so many places I would not be too sure.

Still, Serengeti has one important thing going for it, which sets it apart from the many other excellent game reserves and national parks in sub-Saharan Africa: Serengeti is a self-contained ecosystem, meaning an ecosystem so large it can almost exist without the outside world. In other words, as long as the perimeters of this amazing park are kept intact Serengeti just may defy the odds and never die.

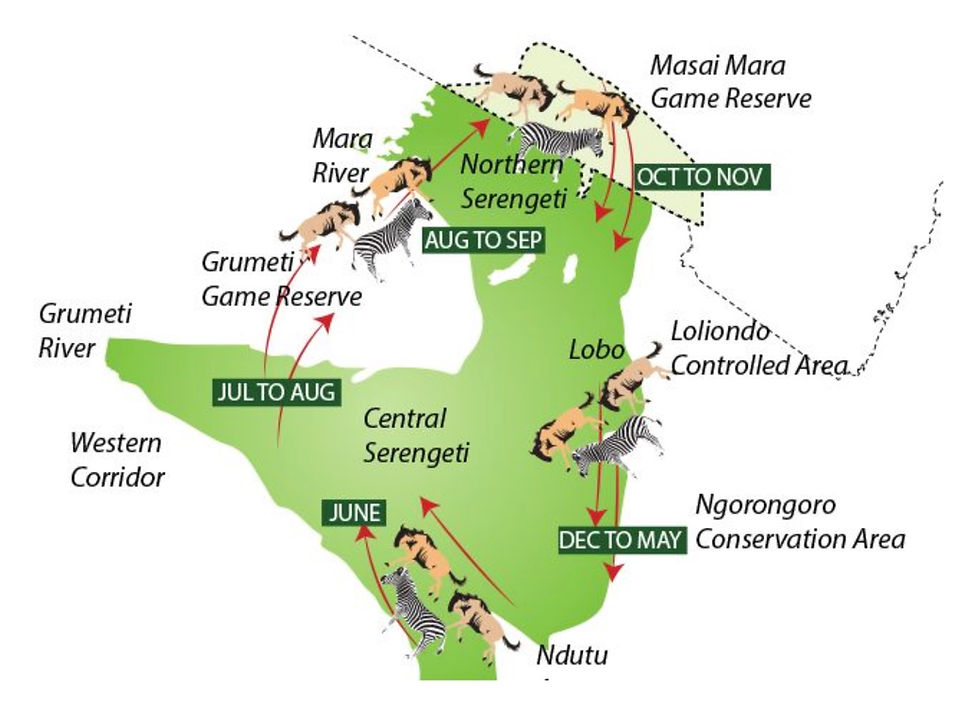

In fairness, Serengeti is not entirely isolated from the rest of the world. Migrating birds come and go with the seasons. There is also occasional trespass of game from the Serengeti onto neighbouring human settlements, leading to conflict. And for two months of the year the great wildebeest migration crosses over into Kenya’s Maasai Mara Game Reserve, although ecologists will point out that the Mara is the part of the same ecosystem as Serengeti; none of the animals that cross the Mara River every year have any clue that they are crossing the human construct we call the national border between Kenya and Tanzania.

As we are visiting the Serengeti in June, we have based ourselves in the Western Corridor, which is a 100 km long tract of land stretching from Seronera in Central Serengeti to Lake Victoria in the west.

The Western Corridor is bordered by the Grumeti Game Reserve to the north and by broken savannah with scattered human settlements to the south-west. A main road cuts through the Corridor from east to west, connecting Seronera with the Ndabaka exit gate in the far West. Numerous small tracks branch off the main road all along the Corridor, reaching into the bush like reddish-brown capillaries.

The Corridor is grass savannah with light bush, scattered low trees, rounded hills, and a couple of rivers, the Grumeti and the Mbalangeti along whose banks grow thick vegetation and tall trees. The Grumeti runs through centre of the Corridor like the string through a pearl necklace. The lands on either side of the river slope gently downwards, making for spectacular views of the plains from the Corridor’s northern and southern edges.

This month large numbers of wildebeest, zebra and various species of gazelle arrived from the calving grounds around further south at Lake Ndutu. By the time the herds reach Kirawira at the western end of the Corridor, the newborns have grown strong enough to match the survival odds of the adult animals. Together, they slowly make their way eastwards through the Corridor before eventually crossing the Grumeti River and then heading north, where the larger obstacle of the Mara River crossing near the Kenyan border awaits in July and August.

The migration is epic in scale. By most accounts, some 1.5 million animals make the trek around Serengeti National Park, spreading out over areas so large that at any one point you rarely see more than 10,000 or 20,000 animals.

Lions feasting in the Corridor (Source: own photos)

The migration is a magnet to carnivores, especially territorial lions that take advantage of the visiting herds to gorge themselves, focusing mainly on the larger prey. Lions can eat upwards of 40 kilos of meat in one sitting. Cheetahs target younger wildebeest, impalas, and other gazelles, while packs of hyenas chase the long lines of wildebeest to pick off sick and injured animals. Vultures and jackals feast on the carcasses left behind.

Carcasses litter the Corridor in June (Source: own photos)

The Serengeti migration never stops. The animals follow a predictable, but imprecise circuit, whose specific path and its timing depend on the rains, which vary year by year though usually not by more than a month or two in either direction. This year the rains arrived early and plentifully, so the migrating herds have not yet felt the need to leave the Corridor.

Like anything in great abundance, the wildebeest are devalued, often taken for granted and even regarded by some with disdain. This is unfair. They may not be the smartest animals on the plains, but they have stripes like tigers, thrive in great numbers, and walk the entire perimeter of the Serengeti ecosystem without a break year after year, from the day they are born until their entrails are torn from their ageing bodies by hyenas and they die in agony abandoned by their own kind. Nature can be brutal that way.

But nature is also beautiful, especially Serengeti. The ground-based bird life is particularly rich, with large numbers of ostrich and an abundance of snake-eating Secretary birds, Ground Hornbills with their characteristic large black bodies and red face masks, and Kori Bustards, Africa’s largest native flying bird.

Secretary Bird, Kori Bustard, Ground Hornbill (Source: own photos)

The fact that Grumeti River is smaller than the Mara makes it less dangerous for the wildebeest to cross, but many still end up in the jaws of the formidable crocodiles that line Grumeti’s banks. There is also a health population of hippopotamus.

Crocodiles and hippos (Source: own photos)

You should never forget to look up. In the blue skies above the Serengeti, you see enormous Marabou storks and many species of vulture circling on thermals only to descent like glide bombers at the sight of a kill on the plains below. Raptors of many kinds also populate the area, including hawks, buzzards, and eagles.

Tawny Eagles, Goshawk, Black-chested Snake Eagle, and a young Martial Eagle (Source: own photos)

Huge troops of baboons roam the plains, formidably strong through sheer numbers. Smaller bands of Vervet Monkeys appear for brief moments and along the riverine forest you can be lucky to spot the rare Colobus Monkey.

All these creatures and countless others, including huge numbers of reptiles and insects live together in the enormous interlocking and self-sustaining ecosystem that is Serengeti. Should the world around this magical place should disappear, Serengeti would still survive. This is why conservationists Bernhard and Michael Grzimek named their famous 1960 book about this national park ‘Serengeti Shall Never Die’.

The End

Comments