Tabora's dark past

- Jan Dehn

- Jul 2, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Jul 29, 2025

The principal purpose of colonialism was to enrich colonisers by exploiting the colonised. To achieve this objective in Africa, the colonisers had to find ways to get into the interior. Since Africa had no roads, the only two ways in were to navigate the rivers and to follow existing overland slave trading routes.

Since Tanzania had no navigable rivers flowing from west to east, the colonisers followed the slave trading routes established by Arabs, particularly the main one running from Ujiji on Lake Tanganyika to Bagamoyo on the coast. The town of Tabora was a key node on this route.

In the 1850s, Tabora was one of the most important places in mainland Tanzania, or Tanganyika as it was then called. It was only eclipsed in political importance by the Zanzibari sultanate. Briefly in the 1850s and again fleetingly in the early 1880s, Tabora was the capital of Tanganyika, first under the Arabs and then under the Germans.

Tabora’s importance stemmed from the fact that the town sat roughly half-way between Ujiji and Bagamoyo, which was a point of confluence of several slave trading routes. Ujiji was main arrival point for slaves and ivory from the vast central African hinterland comprising present-day Zambia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Burundi, Rwanda, and Uganda. Bagomoyo was the port from which ships carried the slaves to main slave market in Zanzibar.

All three towns have since lost their political and economic significance. Today, Tabora is an unassuming provincial centre, Ujiji is a suburb of the town of Kigoma, and Bagamoyo is a small town that mainly hosts conferences for government officials and business people based in Dar es Salaam.

Little was written about Tabora until the mid 1850s, because Africans and the Arabs did not keep written records. In 1857, two Englishmen, Richard Burton and John Hanning Speke, arrived in Tabora and began to record what they saw and heard. They found Tabora to be a major trading hub through which moved vast quantities of Katanga copper, salt, ivory, and hides, but the most important commodity of all was human beings.

A total of 5 million people were taken as slaves in central Africa of which the vast majority came through Tabora, where the slave caravans stopped for supplies and a few weeks of rest before resuming the journey to the coast.

The East African slave trade was horrendous. Half of the slaves taken in central Africa – some 2.5 million people – died en route to the coast. They died from disease, exhaustion, animal attacks, and the violence metered out as discipline by the Arab slavers and their Somali askaris. Thousands lie buried in unmarked graves in and around Tabora.

Visiting Tabora today, it is difficult to imagine the horror and the scale of the slave trade at its peak, although there are a couple of indicators if you look closely.

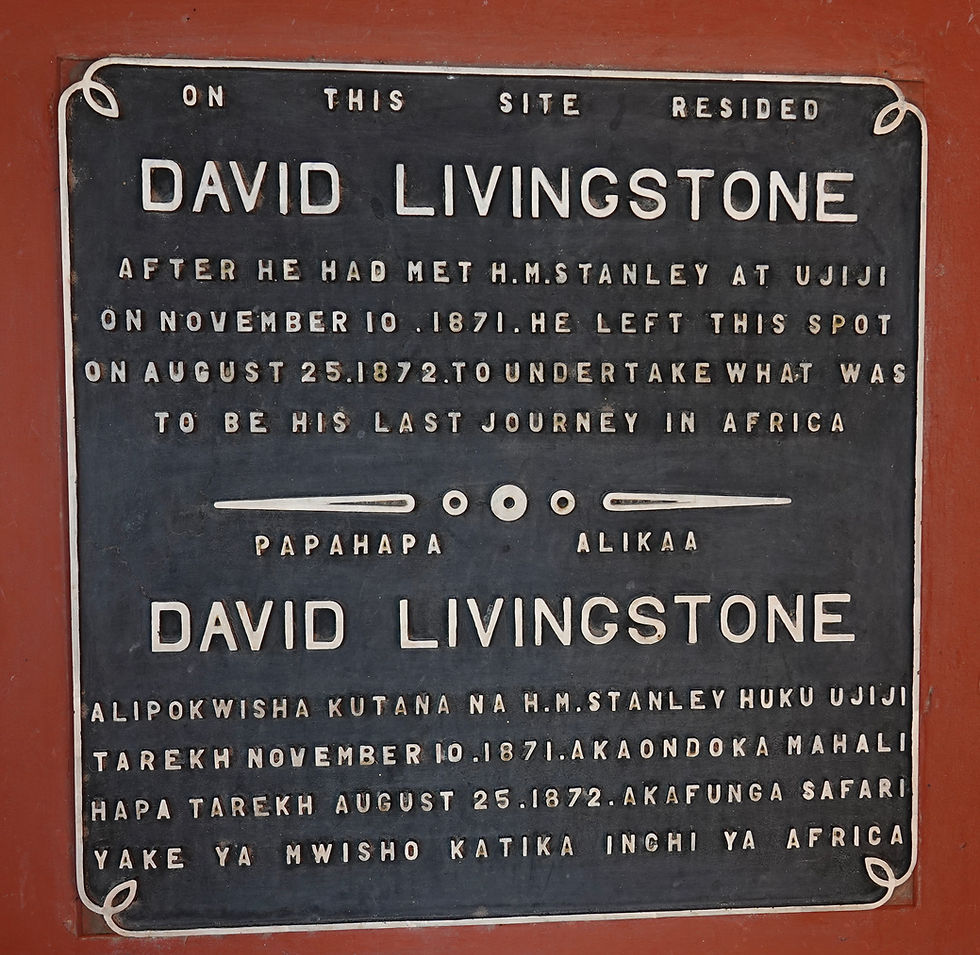

The first indicator is a small museum located at Kazeh, some 11 kilometres south of Tabora. The museum has interesting information about David Livingstone, including a lock of his hair, but the museum administrators have appropriately chosen to focus on the East African slave trade about which far too little is known.

The museum at Kazeh. A mango trees grown from stones of mangos eaten by slaves, the Swahili door marking the entrance to the museum, and a plaque commemorating the arrival of Burton and Speke in 1857 (Sources: own photos)

The museum is housed within the original Arab tembe, which served as the main administrative office for the Arabs running the slave trade through Tanganyika at the time. The large Swahili door, which is the entrance to the museum has chains hewn into the wood lining the edge of the door. This indicates that the owners kept slaves, which was considered an important status symbol at the time. The tembe has a courtyard and rooms for the Arab slavers, storage, the slaves, and administrative and operational functions.

The tembe at Kazakh is of historical significance in addition to being a slave trading hub. Burton and Speke stayed in the building in 1857, when the tembe had only just been built. In 1871, David Livingstone and Henry Morton Stanley also spent a few months there, when their onwards journeys were blocked by Milambo, a local chief challenging for control of the slave trade. The building was also briefly the headquarters for German colonisers. In 1957, one hundred years after its construction, the tembe was officially declared an important historical antiquity by the British colonial administrators.

The other indicator of the erstwhile significance of slave trade in Tabora can be found within the genetic make-up of Tabora’s people. Due to the enormous geographical reach of the slave trade and the unfathomable scale of rape during caravan stopovers in Tabora, the ethnic composition of Tabora’s inhabitants differs markedly from that of other East African towns; to this day large numbers Taborans carry genetic markers that can be traced to populations as far south as Zambia, as far north as Uganda, and as far west as the Congo basin.

The slavery business in Tabora was lucrative and so attracted competition. While the Arabs more or less had a monopoly on slave trading up to the mid-1850s thereafter they began to lose their grip on the business due to internal divisions and serious challenges from the Nyamwezi, Tanzania’s second largest ethnic group, which hails from the Tabora, Singida, Shinyanga, and Katavi regions.

Adhering to a nomadic lifestyle necessitated by poor soil quality, the Nyamwezi had always been traders. When they discovered the value of the Arab slave trade, they began put their trading skills to work first as facilitators for the Arabs, then as uneasy partners in the slave trade, and finally as masters of the slave business.

In the late 1850s, Milambo, a Nyamwezi chief had emerged as leader of all the ethnic groups between Lake Victoria and Lake Rukwa. Milambo was powerful enough to block Arab caravans from entering and leaving Ujiji, thereby enabling him to dictate the Arabs’ trading terms throughout the 1860s. Milambo accumulated considerable wealth, bought guns, and got even stronger. He organised Nyamwezi society into an effective military structure.

After ten years of dancing to Milambo’s tune, the Arabs had had enough. They financed several punishment missions comprising thousands of mercenaries - one accompanied Henry Morton Stanley - to defeat Milambo, but all the attacks failed, leaving Milambo even stronger than he had been before. Only when Milambo died of throat cancer in 1884 at the age of 44 did the Nyamwezi’s iron grip on the slave trade end.

By then, Germany was displacing the Arabs as the most powerful force in Tanzania, aided by campaigns of almost unimaginable barbarity. Unlike the British, the Germans never felt the need to keep up a pretence as far as the true purpose of colonialism was concerned. Like the Arabs before them, the Germans wanted to make money in their new colony and the best way to do so was to access to the interior, regardless of the cost in African lives.

Unwilling to walk from Ujiji to Bagamoyo as the Arabs had done, the Germans began to build a railway in 1888 along the original Arab slave route. The only departure from the original route was to replace Bagamoyo with Dar es Salaam and Tanga due to their natural harbours. The railway was completed in 1914 and a fine new hotel was built in Tabora to mark the occasion.

The fading charms of the Orion Tabora Hotel, built for the Kaiser, host to an English princess, and honouring a slaving Nyamwezi chief (Source: own photos)

Unfortunately, just as the German Kaiser was about to travel to German East Africa to inaugurate the hotel, World War I broke out, spoiling the party. By 1918, the Germans were out of German East Africa and the British were in.

From the start, the British took the job of opening up the interior of Africa for exploitation to a whole new level, epitomised by Britain’s ambitious programme of bringing in foreign settlers to occupy the best arable lands and its obsession with locating the source of the Nile.

The British hoped that by finding the source of the Nile they build a trade route that would put all other trading routes to shame, one that would go all the way from Egypt to the Great Lakes region in central Africa. As the British were also expanding northwards from South Africa and Rhodesia, the British hope was to eventually control all of Africa from Cairo to Cape. No other coloniser ever came close to such ambition.

With great ambition comes great violence and hence the need for great obfuscation. Unlike the Arabs and the Germans, the British were highly skilled in hiding their monstrous intent behind a fig leaf of ‘civilising missions’. The two most important fig leaves were missionary activity and the abolition of slavery.

No single individual personified the British hypocrisy about their colonial conquests more than David Livingstone. To this day, children are taught in school that Livingstone was an indefatigable missionary and anti-slavery crusader, who gave his life in deepest darkest Africa to civilise the primitive natives.

Reality is different. From day one, Livingstone was motivated by an ambition to advance British commercial and colonial expansion. His obsession with empire-building and commercial exploitation of Africa is evident in all three of his big endeavours in Africa. In 1852, he abandoned missionary activity in Angola after finding no viable trading routes into the interior. In 1864, after seven years of trying, he abandoned missionary activity in the Zambesi basin, not because he could not find converts, but because he discovered that the Zambezi river was not navigable for commercial purposes. And from 1866 onwards, he dedicated the rest of his life in the Lake Tanganyika region not, as he alleged, to winning souls, but to discover the source of the Nile, the biggest prize of all.

By the time Livingstone set his sights on the source of the Nile, even his bosses in the London Missionary Society (LMS) felt "restricted in their power of aiding plans connected only remotely with the spread of the Gospel" (see here). Unwilling to keep up the pretence any longer, Livingstone left the LMS and became her majesty’s roving council instead, exposing the lie behind his protestations of missionary zeal.

The museum at Kazeh is the last place Livingstone is known to have lived before went into the bush for the final time and died. When all the sugar-coating surrounding his life is removed, Livingstone’s purpose was really no different from that of the Arab slave traders, Milambo of the Nyamwezi, and the German colonialists. He wanted to access Africa’s riches with the aim of exploiting them. This is why he walked the Arab slave routes. This is why he was in Tabora.

Livingstone did not live to see the fruits of his labour, but his post-humous glorification led directly to the founding of a plethora of major Christian missions in Africa. These missions spearheaded Europe’s "Scramble for Africa", which eventually subjugated almost the whole of Africa to decades of European Apartheid rule and the near-complete destruction of countless African cultures.

In my view, Livingstone was one of history’s devious little shits, not a hero at all. He portrayed himself as a self-sacrificing slavery-fighting moral authority, but in reality he was obsessed with power and Empire.

As for the source of the Nile, Africa played a trick on the British. The Nile emerges from Lake Victoria at Jinja in Uganda, but Lake Victoria is not the river's ultimate source, which the British so desperately wanted to control. It turns out about 20% of the water in Lake Victoria comes from a plethora of smaller rivers that empty into the lake, including the Kagera, Sio, Nzoia, Yala, Nyando, Sondu Miriu, Mogusi, Migori, Grumeti, Mara, and the Mbalageti. The remaining 80% comes from...wait for it....direct rainfall! Control that, colonialist scum!

The End

Comments