Standing up for nature

- Jan Dehn

- Jul 1, 2025

- 6 min read

To get a sense of what the future holds for the environment in developing countries look no further than what happened to nature in industrialised economies.

In Denmark, a relatively environmentally conscious developed economy only 15% of the land is covered by trees of which the vast majority is secondary forest grown for industrial purposes. The remaining 85% is either paved over as cities and roads or hyper-processed using intensive agricultural practices. In the Netherlands, forest cover is only 11%. Apart from Canada and Russia, most developed economies have little or no primary nature left at all. The reason is simple: As countries develop, they tend to destroy their primary environments.

Like the rich countries before them, today's poor countries are also likely to prioritise economic development to the detriment of the environment. Political pressures to raise dismally low living standards are simply too overwhelming; when the voting public scrapes by on a Dollar day politicians cannot object to building roads, constructing health care centres or schools, and opening land to agriculture.

Larger birds in the swamps west of Serengeti (Source: own photos)

Unfortunately, if poor countries destroy their nature the same way as rich countries did then the world as a whole has a really serious problem. There was still plenty of virgin biodiversity left in the developing world when today’s rich countries moved up the economic ladder, but when today’s poor countries destroy their remaining biodiversity there will not be any left at all. All the world's last remaining reserve ecosystems will disappear.

Think for a moment what this means in practice: There will no longer be an Amazon jungle once Brazil’s living standards have reached Danish levels. There will no longer be a Serengeti National Park by the time Tanzania has achieved upper-income status. And so on across the developing world.

Small birds in the swamps west of Serengeti (Source: own photos)

When the last remaining self-sustaining ecosystems in developing countries have been sacrificed on the altar of development we will be left with small, artificial, and disconnected theme parks containing mere slivers of the wildlife that once existed. Closely managed by humans, these zoos will be depressing and pathetic testaments to a lost world.

But that is not all. The biggest problem is not what we will have lost, but what we may yet lose. The problem with preserving only tiny fractions of nature rather than proper ecosystems is that all the erstwhile interconnectedness and evolutionary dynamism of ecosystems is lost. And with this loss comes fragility. Life on earth itself will be at risk.

More birds in the swaps west of the Serengeti (Source: own photos)

In fact, biodiversity is ultimately even more important than the climate. In a world, where 99% of biodiversity has been exterminated and where the remaining bits of nature are disconnected, it will only take very small shocks – say outbreaks of disease – to wipe out all remaining life on this planet. Populations sizes and the genetic variation across the few surviving species will simply be insufficient to ensure that at least some species survive if serious shock occur.

All of this means that the ongoing environmental destruction in poor countries today is not just a poor-country issue; it is a global issue. If so, what can be done to stop the damage?

The good news is that the problem can actually be solved very easily. Rich countries simply need to compensate poor countries for not developing, enabling them to obtain higher living standards despite not destroying their globally vital ecosystems.

Long-crested Eagle having a meal (Source: own photos)

In practice, rich countries would have to transfer sufficient resources to, say, Brazil as compensation for not cutting down the Amazon to enable Brazilians to continue to enjoy rising living standards. Similarly, every farmer living on the outskirts of Serengeti should be given funds for not turning the savannah into farmland.

Unfortunately, such transfers are not taking place. Voters in rich countries are loath to transfer funds to vulnerable groups within their own societies, so the idea they would send loads of money to brown people in poor countries is a complete non-starter.

This state of affairs has led many poor countries to conclude that if they want to protect their remaining ecosystems they must do so at their own expense. Unsurprisingly, this has immediately given rise to domestic political conflict, pitting local populations, who want economic development against local conservationists, who want to protect environment.

Other swamp life (Source: own photos)

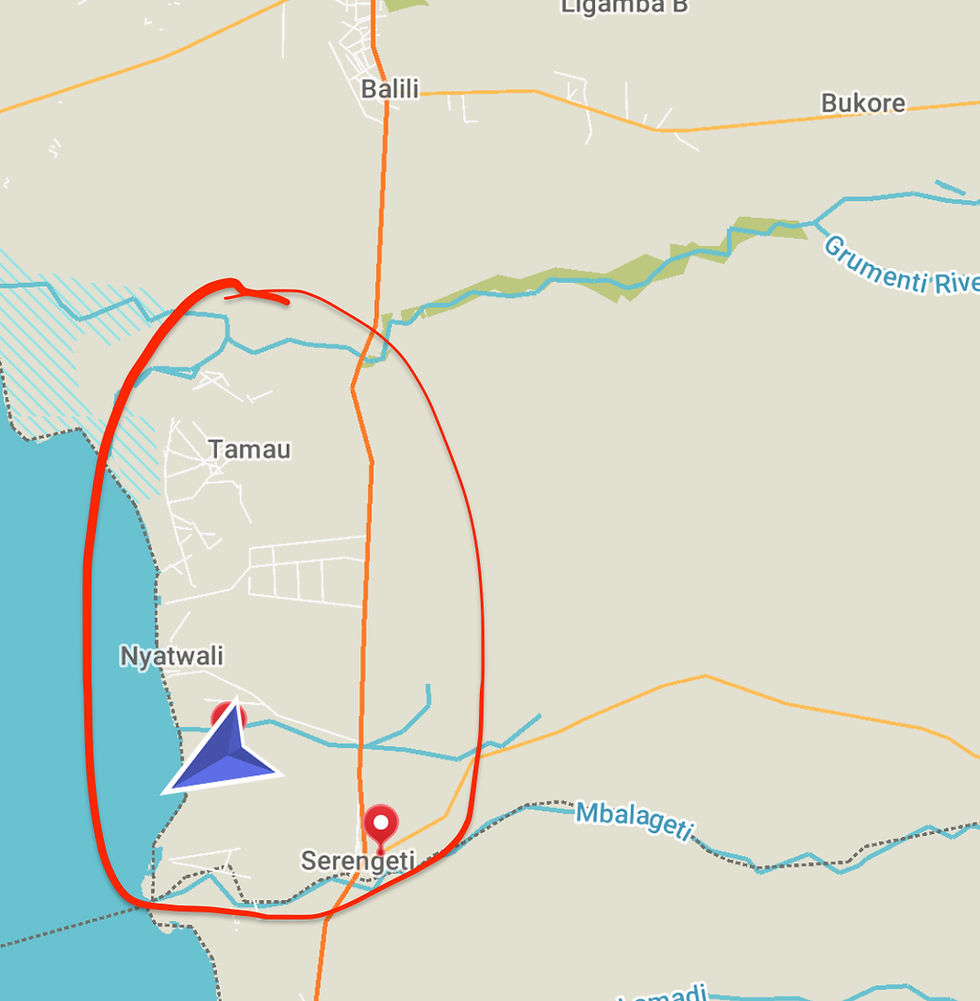

Tanzania is an interesting case in point. Tanzania is home to the Serengeti National Park, which is one of the world’s last truly self-sustaining ecosystems - see here. The Tanzanian government recently took the bold decision to expand the Serengeti National Park by a few kilometres in a westerly direction in order to extend the park’s so-called Western Corridor all the way to the shores of Lake Victoria.

The expansion will add two unique ecosystems to Serengeti's savannah lands, namely an extensive swamp with extremely rich bird life as well as the lake ecosystem of Lake Victoria itself. Once completed, the extension will create an unbroken protected tract of nature stretching from Ngorongoro in the east to Lake Victoria in the west.

The land area involved in the proposed extension is relatively modest. At its western extreme, the Western Corridor narrows to just 11 kilometres in width between the Mbalageti and Grumeti rivers. The existing park border is about 7 kilometres from the lake, so we are taking about some 77 square kilometres, which needs to be cleared of inhabitants in order to accomplish the park extension. In addition, a fly-over on the highway connecting Mwanza with the Kenyan border will have to be constructed to enable wildlife to move freely from park to lake without getting hit by fast-moving cars and trucks.

Understandably, there is resistance to the proposed relocation from locals in the area. Those living in the affected area have lived anywhere else and many are highly specialised fishing and pastoral people with very close cultural ties to land in which their ancestors are buried.

The Tanzanian government is not insensitive to these complications and has opted to compensate those required to leave. Still, few of the deportees have any understanding of how to manage lump sum payments. Many have also found it difficult to build entirely new lives in places and environments that are different from the ones they left behind.

What the Tanzanian government is inflicting on these people is what we, humans, inflict on nature all the time, almost everywhere.

Evicted homes being re-absorbed by nature (Source: own photos)

I recently visited the area in question. During my visit, a government aircraft flew over the area at low altitude taking photographs to monitor progress of the evictions. The evidence of evictions is visible in the form of abandoned shells of buildings, which once housed families. They now stand empty, ghostlike with their doors, windows, and corrugated iron roofs removed, amidst rapidly encroaching bush.

Can Tanzania’s attempt to expand the Serengeti National Park be replicated elsewhere? It is not clear to me at all, because very special conditions exist in Tanzania. For one, the country is ruled by a strong single-party government, which has been in power since independence and ordinary Tanzanians, for the most part, seem to do what they are told.

Also, this is not the first time Tanzania has relocated people by force. The country’s first president, Julius Nyerere, relocated millions of people from scattered rural communities into newly built so-called Ujamaa villages in the name of development. The rationale for Ujamaa was that a poor country like Tanzania could not afford to provide essential public services (schools, water, electricity, health care, communication, transportation, and commercial services) to countless tiny communities dotted across vast areas, but by corralling these people into newly built villages it would be able to extend such services to everyone. That was the idea, anyway.

The Tanzanian government is now using the same approach to depopulate the area designated for the Serengeti expansion, this time in the name of the environment. While I feel empathy for the departing families, ripped as they are from the lives to which they have become accustomed, I also find myself applauding the Tanzanian government for daring to stand up for nature.

It is time someone did.

The End

Comments