US long-term economic growth: heading up the creek

- Jan Dehn

- Oct 16, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Oct 17, 2025

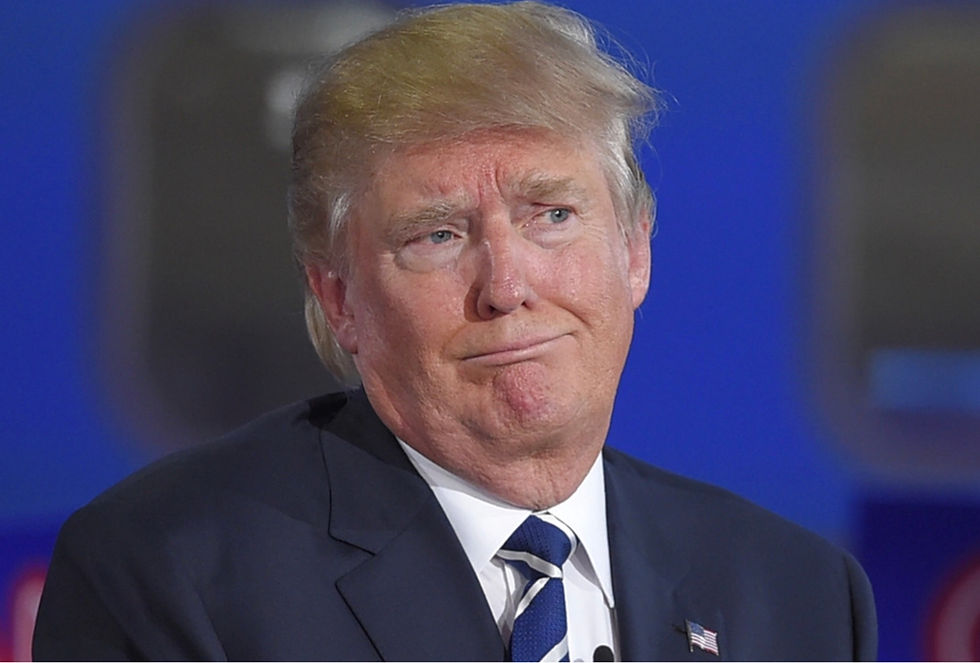

Not the best outlook for long-term growth (Source: here)

Economic growth is what lifts nations out of poverty. The theory of economic growth is therefore one of the most important subjects in all of economics. In this note, I examine the drivers of sustained, long-term economic growth and ask how well – or badly – they align with current economic policies in the United States.

Due to the enormous political importance attached to growth, politicians the world over seek to stimulate growth in various ways, such as increasing government spending or leaning on the central bank to cut rates or by intervening in specific sectors in order to ‘pick winners’.

The Trump Administration is no exception. However, interventions rarely end well. They are a bit like pissing in your pants to keep warm; the initial warm fuzzy feeling soon gives way to regret.

_____

Economic theory has established three fundamental sources of economic growth, namely accumulation of capital (more machines), accumulation of labour (more workers), and technical progress. Technical progress is best thought of as ways capital and labour combine to produce output; when technical progress advances then given stocks of capital and labour produce more output.

Empirical evidence shows the majority of economic growth in Western economies in the past hundred years is due to technical progress. It has therefore been somewhat frustrating for students of economic theory that the profession struggled for a long time to explain exactly how technical progress brings about growth. As recently as 1990, when I began my studies in economics, economists still had no idea how innovations at firm-level led to sustained productivity growth in the economy as a whole.

This all began to change in 1992, when economists Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt published a paper titled “A Model of Growth Through Creative Destruction”. The model, which expanded on historical insights by Joel Mokyr, explicitly linked firm-level innovations to macroeconomic productivity growth and hence GDP growth itself.

This week, Aghion, Howitt, and Mokyr were awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics for their contributions to the understanding of long-run economic growth. They demonstrated that sustained growth derives from firm-level innovations. Their insights give us a great benchmark against which to evaluate long-term growth policies of current governments, including those of the Trump Administration.

To understand the Aghion, Howitt, and Mokyr model, we first have to recognise that there are two distinct types of knowledge. The first type is the hands-on techniques we observe in skilled craftsmen, such as blacksmiths, carpenters, electricians, engineers, etc. The second type of knowledge is what theoreticians and researchers generate in universities, commercial labs, and think tanks. For most of history, these two bodies of knowledge have existed in splendid isolation, which, it turns out, is why so little growth was achieved until the Industrial Revolution.

What changed in the Industrial Revolution was that the two types of knowledge were combined for the first time to produce actionable, practical, and money-making novel ways of doing things. Or to put it more succinctly, firm-level innovations. Given that the raison d'être of private firms is to make money, Aghion, Howitt, and Mokyr showed that under the right conditions firms will deliberately set out to innovate as it helps them to make money.

To see how, consider what happens when a firm successfully innovates. The innovation enables the firm to achieve temporary monopoly power, wherefore it can sell the superior product at a mark-up over and above the cost of producing the good. Moreover, competitor firms will lose market share or even go bust as demand for their now sub-standard products wanes.

The innovation process is therefore exceptionally violent at firm-level, characterised by simultaneous destruction and creation as new technologies again and again displace older ones, propelled forward by innovation in order to achieve temporary super-normal profits.

At the macroeconomic level, the impact on economic growth depends on the size of the innovations and how frequently they occur. Big markets with many innovators grow more than small markets with few innovators. There is strong empirical evidence that firm-level creative destruction takes place on a massive scale in modern capitalist economies. In the United States, for example, some 7-8 millions jobs are destroyed and created every quarter, which means that roughly half of all jobs in the US economy turn over every half a decade (see here).

Why, you may ask, does such a violent process of destruction and creation at firm-level not lead to instability at macroeconomic level? The answer is that modern economies, such as the Unted States, are comprised of thousands of sectors. Innovations take place within these sectors in random, often incremental, and usually uncorrelated ways, so they average out across the economy as a whole. This is why observed growth rates at macro level tend to be stable, even smooth over long periods of time (about 2% per annum in real terms in the case of the United States).

Interestingly, the Aghion, Howitt, and Mokyr model also goes a long way towards explaining why low-income countries linger for long periods in poverty and struggle to achieve escape-velocity. Poor countries stay poor because they do not have the large markets with many sectors required for sustained innovation-led productivity growth. Indeed, most poor countries are simple two-sector economies made up of a large informal sector with near-perfect competition and a small formal sector dominated by a tiny number of near-monopolies. This is the worst possible constellation for sustained innovation-led growth, because neither highly competitive informal sectors nor the highly monopolistic formal sectors deliver innovation. More on the reasons why shortly.

_____

What are the main policy implications of Aghion, Howitt, and Mokyr’s insights about economic growth? How, exactly, should, say, the United States government run the economy? As a guiding principle, the Aghion, Howitt, and Mokyr model implies that governments should maximise the number of innovations in the economy and the profitability of each innovation, because this is what leads to the highest rates of productivity growth and in turn produces the biggest improvements in human welfare.

Since innovators – people with good actionable ideas – are distributed randomly in the population the best way to maximise innovations is simply to maximise the number of people in the economy. Governments should therefore open borders to immigration, which expands the size of the talent pool from which innovators emerge (a larger labour force also contributes directly to economic growth).

Governments should also remove barriers to cross-border investment and trade. Tariffs are particularly bad for growth, because they split big connected markets into smaller isolated ones, which means that the amount of profit firms can make from innovations is correspondingly smaller. In fact, the ideal situation is to have a single global market without any barriers at all, but, barring that, at least governments should aim to enter into large trading blocks, such as the European Union (EU). The United Kingdom is therefore clearly heading the wrong way in leaving the EU.

Competition policy is very important in the Aghion, Howitt, and Mokyr growth model. It says governments should combat monopolies, because monopolies have no incentive whatsoever to invest in R&D. Monopolies make money by over-charging consumers, which they can do because they are able to prevent entry from other firms. Clearly, a market with only one firm does not frequent turnover, or ‘churn’, so there is zero innovation.

On the other hand, governments should also avoid perfect competition, because firms without any market power whatsoever are unable to prevent other firms from copying their products. Unable to recoup the costs of innovating, they do not innovate at all.

The ideal policy with respect to competition is the middle ground between monoploy and perfect competiton, where companies have temporary monopoly power to enable them to profit from their research, but where new entry soon erodes away the innovator’s monopoly power.

Recent events in the market for weight-loss drugs illustrate the ideal balance in competition policy. Danish medical giant Novo Nordisk enjoyed monopoly power for a time after the launch of its highly innovative weight-loss drug Wegowy. However, new entrants soon began to eat away at Novo Nordisk’s market power. While Novo Nordisk made enough money to recoup the cost of innovation, it ultimately lost its monopoly position. This is the ideal situation from a public policy perspective, because you get the innovation, you get the rapid productivity growth, and you minimise monopoly power with only a very light regulatory touch.

The Aghion, Howitt, and Mokyr growth model also has important implications for other areas of policy. You generally want to avoid boom-bust fiscal policies and excessive levels of debt, because they give rise to crises, which depress investment and risk-taking in general. You do not want to tamper with central banks either, because innovators do not like uncertain interest rate prospects, which can make it very difficult to estimate returns to innovation. Monetary policy should therefore be conducted by an independent central bank. As for exchange rate policies, you generally want floating rates, since they reduce (though do not entirely eliminate) the risk of sustained real exchange rate mis-alignment, which usually leads to violent and disruptive shocks, again, impeding innovation.

Industrial policy, that is direct government intervention in sectors of the economy, is often undertaken with the explicit aim of supporting so-called ‘national champions’. However, this is a bad idea according to the Aghion, Howitt, and Mokyr growth model, because when governments offer protection to certain sectors over others they create incentives for firms to lobby rather than to innovat, stifling dynamism and growth.

It is also critical that governments adopt a hands-off approach to education policy. School curricula should be evidence-based and inclusive, with no religion whatsoever in the class room. Universities should be independent and completely free to define their research agendas. They should also be free to attract the best talent from anywhere in the world.

Needless to say, rule of law, respect for human rights, and democracy are extremely important, since their dismantling can push entire societies into deep social conflicts, which ultimately backfire very badly on the business environment.

Finally, in order to enable innovation to flourish as much as possible, it is critical that every child is given the opportunity to realise its full potential, regardless of race or class. This is why basic social safety nets and other policies that prevent excessive income inequality are good for growth.

_____

Now, how do the policies of the current United States Administration stack up against these policy prescriptions arising from the insights of this year’s economics Nobel Prize winners? Is the Trump Administration on the right track as far as economic growth is concerned, or is Trump heading up the creek without a paddle?

Unfortunately, it would seem that the US government is going completely off the rails as far as long-term economic growth policy is concerned. Specifically, the Trump Administration is going wrong by:

· Closing the US borders to immigrants and actively deporting large numbers of immigrants – BAD NEWS FOR GROWTH

· Putting up tariffs and isolating US market from the rest of the world – BAD NEWS FOR GROWTH

· Favouring monopolies and failing to apply existing anti-trust policies to tech giants – BAD NEWS FOR GROWTH

· Building up massive public debt – BAD NEWS FOR GROWTH

· Favouring the ultra-rich over the poor in tax policy – BAD NEWS FOR GROWTH

· Leaning heavily on the Federal Reserve to cut rates – BAD NEWS FOR GROWTH

· Promoting US companies over foreign rivals – BAD NEWS FOR GROWTH

· Intervening in US education establishments, especially universities as well as promoting religion in schools – BAD NEWS FOR GROWTH

· Discouraging foreign talent from studying in the US – BAD NEWS FOR GROWTH

· Removing basic social safety nets for low-income groups – BAD NEWS FOR GROWTH

Most concerning, the Trump Administration appears to be deliberately undermining the rule of law, human rights, and democracy itself. As I type these words, the Trump Administration is undermining the US economy’s long-term growth potential. While Trump’s policies may or may cause an imminent crisis, they will bring about the definitive end to US global hegemony unless Trump changes tack. Asia in general and China in particular will inherit the mantle of global growth leader. Ironically, this is not just because Asia pursues better growth policies. A big contributing factor is that the actions taken by the Trump Administration to combat Asia’s rise are already backfiring badly on the US economy itself.

The End

Comments