The pillage of Potosi

- Jan Dehn

- Dec 19, 2025

- 9 min read

Updated: Feb 5

The face of greed: mural hanging over the entrance to the Mint House in Potosi (Source: own photo)

Greed was always the main motivation behind the colonisation of Latin America. For hundreds of years, greed manifested itself in countless ways in Spain's American possessions, but nowhere was avarice taken to greater and more cynical extremes than in the Bolivian silver-mining town of Potosi.

A mere swamp before the arrival of the Spanish, Potosi would become one of the greatest cities in the world within mere decades of the discovery of silver. Pieces of Eight as the coins struck in Potosi's Mint House were known became the first truly global trading currency.

Yet, Potosi's stellar rise also inflicted devastating costs on the local population. In human terms, the price of silver mining in Potosi was incalculable. When the silver boom ended, Potosi was left with little else than the ghosts of millions dead. Having once produced the greatest wealth the world had ever known, Bolivia was left a broken country and remains the poorest nation in Latin America to this day.

When Columbus stumbled upon the Americas in 1492, the Spanish had no idea what they would find. In fact, they had not even expected to find land, because they were on their way to India. After discovering gold, silver and precious stones in Mexico, Peru, and Colombia, the Spanish quickly became obsessed with accumulating wealth. Once the Spanish Crown discovered the full potential to loot in the New World, it forgot all about India and instead assigned conquistadores a simple mission in South America: enrich Spain as much as possible, as fast as possible, regardless of the cost to the local population.

The conquistadors began to raid in the north of the continent and then slowly pushed south, reaching Bolivia in 1538. They set up camp in a pleasant valley at present-day Sucre, some 155 kilometres north-east of Potosi town, and began prospecting in the nearby areas.

Pleasant Sucre (Source: own photo)

The Spanish were not the first to mine the region. Prior to their arrival, Huayna Capac, who ruled the vast Inca Empire and fathered the last Inca Emperor, Atahualpa, had mined silver at Porco, which is about fifty kilometres south-west of Potosi town.

Still, it would take seven years for the Spanish to hear about silver at Potosi and it happened through a sheer stroke of luck. The Spanish might never have learnt of Potosi had it not been for a llama herdsman, who, in 1545, was tending his animals in a swampy field, which once existed roughly where Potosi's main square sits today.

As his day was drawing to a close, the herdsman discovered to his dismay that he was missing a few animals. Surmising they must have gone up the towering mountain adjacent to the swamp, he climbed its slopes and eventually found his llamas, but by then it was too late to go down, so he set up camp, lit a fire to keep warm, and went to sleep.

The next morning the herdsman noticed a trickle of shining metal flowing from the base of the camp fire. When he got back to his village, he told a friend about his discovery. The friend advised him to tell the Spanish, who were known to execute anyone found to have withheld information about precious metals and stones.

And so it was that a humble herdsman in a remote part of central Bolivia, by following a friend's advice, handed Spain the keys to the largest silver deposit in the world. The mountain above the swamp would soon become known to the world as Cerro Rico, the rich mountain, while to the Indians, who would die mining it, it would forever be known as 'the man eater'.

The discovery of silver on Cerro Rico caused immediate chaos. The precious metal could literally be scraped off the top soil, so every Spaniard in the area rushed to the mountain to get rich quick. It was the law of the jungle. There were no authorities to issue concessions. There was no infrastructure to process and transport the silver. There was no police to protect property rights. And, of course, there were no means for the Spanish crown to tax the booty. Worse, the frequent fights, which broke out between silver-fevered conquistadores threatened to shatter the unity, which was essential to maintaining Spanish control in the territory.

By the early 1570s, the Spain Crown had been fully briefed about dangers and opportunities of Potosi. Determined to stamp out anarchy and put silver production at Cerro Rico on an industrial footing, Spain dispatched Lima-based Viceroy Francisco de Toledo, the highest authority in the Spanish colonies to Potosi to put things right.

Toledo's top priority was to secure a steady supply of labour to the mines. To this end, he adopted a version of the Mita system, which the Incas had used to implement public works. Under the Mita system, all able-bodied men were required to provide a certain number of hours of labour to the Inca empire each year, usually a few days to build infrastructure.

Toledo twisted the Mita system beyond all recognition, effectively turning Indians into slaves. From the mid-1570s onwards, Spain forced 13,000 able-bodied Indian men to work in Potosi's mines every year. Most never made it out. Unlike the Incan Mita, the work commitment under Toledo's Mita was open-ended. Moreover, conditions were inhumane in the extreme, both inside the mines and along the gruelling processing path that ended in the Mint House in Potosi town, where the silver coins were struck.

It is difficult to exaggerate the cynicism of Toledo's Mita system and its impact on Indian life in South America. It drained male labour from an area spanning Quito in the north to Buenos Aires in the South, from the Pacific coast to the Amazon lowlands. Suffering was not confined solely to mining operations; the loss of male labour collapsed food production in the local Indian communities, which led to widespread famine. All told, some 7 million Indians died at the hands of the Spanish during Colonial rule.

Having secured a supply of labour through his Mita system, Toledo turned his attention to improving the efficiency of silver production. He had 10 kilometres of viaducts built that connected lakes in the high mountains to 130 downstream processing mills. Each mill powered hammers that pounded rock from the mountain into powder from which the silver was extracted using mercury amalgamation. The mercury method was far more efficient than earlier systems, but it also led to the illness and death of thousands of Indians from metal poisoning.

A few of the remaining sections of the viaduct and water mills implemented by Toledo (Source: own photo)

Each of the 130 processing plants produced silver ingots, which were then carried on the backs of Indian slaves back up the hill to the Mint House (Casa de la Moneda), which Toledo had had built in Potosi town. In the Mint House, the silver ingots were flattened using large German-made mule-powered rollers and then cut into coins and stamped with the official logo of the Spanish crown.

These were no ordinary silver coins; they were Pieces of Eight, or Spanish Dollars as they were also known. Due to the volume of these coins, they were soon adopted by businesses the world over as the first truly international trading currency. For the next two centuries, all international transactions were done using Pieces of Eight until they were gradually replaced by Pound Sterling.

The landscape around Potosi (Source: own photo)

The silver coins were transported from Potosi to the Pacific coast via two routes. The main route was 780 kilometres long and wound itself through the mountains north of the Salar de Tunupa (Uyuni salt flats) to the port of Arica. The other route was 890 kilometres long and went south of the salt flats to Antofagasta. In the early days, the silver was carried by enslaved Indians, but llamas, which could carry 40 kilos of silver each were soon found to be more efficient than people. Trains were not introduced until the late 1800s, many years after the end of colonialism.

Old steam engines and rolling stock at Uyuni from where the line heads to the Pacific coast (Source: own photos)

You can still trace the rutas de la plata (silver routes) by the names of the towns between Potosi and the coast. The towns have large churches and bear Spanish names, such as San Cristobal, San Pedro, and San Agustin. The Spanish were keen to keep up the appearance of being devout Catholics, so they insisted on rest and prayer on Sundays. To facilitate this, they constructed a new town along the silver route at points that marked six days' march by the llamas.

The Spanish church at San Cristobal (Source: own photo)

From the ports of Arica and Antofagasta, the silver was shipped in galleons to Acapulco in Mexico. In Acapulco, half the silver was put on galleons and sent to Spanish Philippines, where the coins entered circulation as payment for silk, porcelain, and spices from China, Japan and elsewhere in East Asia. These luxuries were then shipped back to Acapulco and, along with the rest of the silver, transported by ship to Panama City, where the cargoes were put on mules and logged across the Isthmus to the town of Colon on the Caribbean side. When Panama City was under threat from pirates, which happened quite frequently, the silver and the Asian luxuries were instead transported across present-day Colombia south of the Darién Gap to Cartagena de Indias. The treasures were then shipped from there to Seville in Spain via Cuba and the Azores.

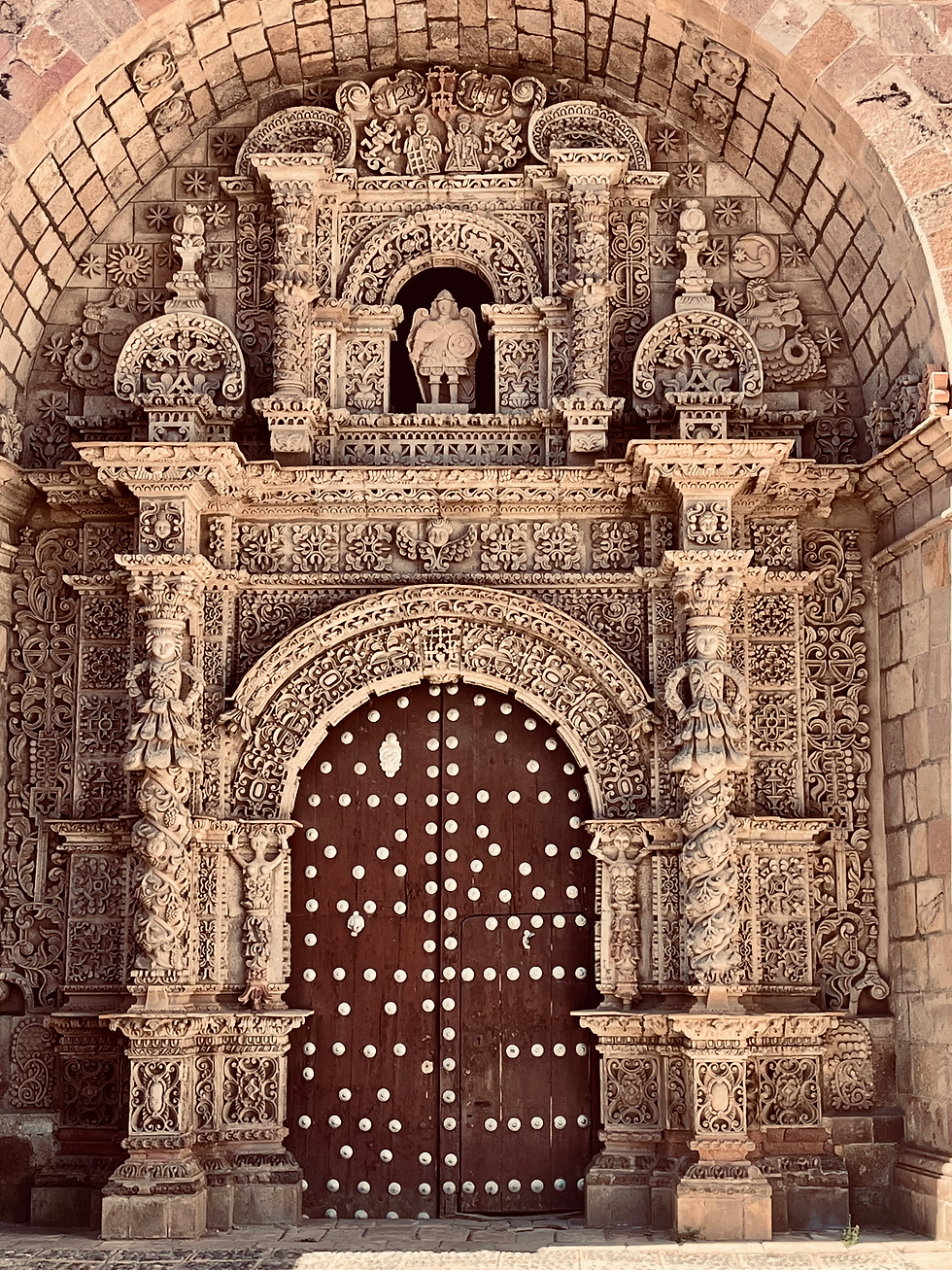

Perhaps the finest Baroque church facade in all of Latin America can be found in Potosi (Source:own photo)

Toledo's infrastructure investments transformed mining at Potosi. By the time production of silver peaked in the 1600s and 1700s, Potosi had become the largest city in the New World with a population exceeding 200,000 inhabitants. Potosi was the richest city on Earth. As befits a city of such standing, Potosi boasted shops with unimaginable luxuries, salons, theatres, and, of course, churches whose number were only exceeded by the brothels that catered for every conceivable taste. Churches and brothels were often located on the same street, mere meters apart.

Former brothels (with green balconies) adjacent to one of Potosi's churches. Cerro Rico rises in the background (Source: own photo)

Like elsewhere, the Catholic church in Potosi ingratiated itself with power and money by blessing the lethal mining business in exchange for large quantities of silver. So intimate was the connection between the church and mining in Potosi that, uniquely, the Virgin Mary was often painted wearing in a large dress, whose triangular shape exactly matched the shape of Cerro Rico as shown in the paintings below, which are on display in the former Mint House, now a museum.

Virgins Mary wearing Cerro Rico mining dresses (Source: own photos)

By 'sanitising' the genocidal exploitation of Indians in the mines, the churches of Potosi were rewarded with so much wealth that when Antonio José de Sucre, Bolivia's first president, found the state coffers empty after years of war, he was able to fund all the new nation's public services (schools, hospitals, and the army) with the treasures he confiscated from Potosi's churches.

Potosi church ornaments in pure silver (Source: own photos)

All official business pertaining to Potosi was conducted from Sucre, which had been granted the status of Audiencia de La Plata by the Spanish crown. Audiencia gave Sucre overall administrative control over an enormous area that covered not only Potosi and all of present-day Bolivia, but also Paraguay, Northern Argentina, Uruguay, and large sections of Peru. This level of power, it was felt, was required to ensure Potosi did not get too big for its boots. Managing things from Sucre also helped Spain's image; pleasant, clean, religious, and very Spanish in architecture, Sucre put a civilised face on the mining industry, which, in reality, was one of extreme greed, ruthless exploitation, and violence. To this day, many well-to-do business people and officials still live in Sucre even though their main businesses are in Potosi.

Potosi pedestrian street with Cerro Rico in the background (Source: own photo)

Sixty thousand tonnes of silver were taken from Cerro Rico. Wealth extraction remained Spain's core objective in Latin America right up until Spain lost the War of Independence in 1809. Potosi was the very last place the Spanish let go of in Latin America, underlining the enormous value Spain attached to the province's legendary silver mines.

Being built on commodities, Potosi's fortunes were always going to be closely tied to the price of silver. When silver prices tumbled in the late 1800s and production shifted to tin in northern Bolivia Potosi's decline was as spectacular as had been its rise. The economy collapsed and the city depopulated. Spanish coins lost their status as global reserve currency in favour of Pound Sterling as Britain proved far better than Spain at profiteering in the new modern, industrial age.

Throughout the second half of the 1800s, Britain lobbied hard for greater control over rich guano and copper deposits in the Bolivian coastal zone north of Chile. Aided in all likelihood by British engineers, Chile took a significant chunk of Bolivian mineral-rich territory in the War of the Pacific (1879–1904), which also meant that Bolivia lost access to the sea. In 1952, in the wake of intense political pressure from unions, the Bolivian government nationalised all mining and rail industries in the country, but to no avail. By the 1980s, the Bolivian government was bankrupt and had to sell its railways to Chile, adding insult to injury.

When looking back at the history of Potosi, it is thought-provoking how little Bolivia has to show for centuries of exploitation. The Spanish did not care about the Indians and left almost nothing of value behind. Bolivians are still among the poorest people in Latin America. While Potosi remains an important mining centre, the excesses of the colonial days are long gone. The only really obvious reminder of the centuries of exploitation in Potosi is Cerro Rico itself. Today, the mountain has more holes than a Swiss cheese and the top has partially collapsed onto itself, but somehow Cerro Rico still manages to cast a long and sinister shadow over Potosi and the rest of Bolivia.

The End

Comments